James Ransone III: Life, Career, and Death

James Finley Ransone III never built a career around reassurance. He did not present himself as aspirational, charming, or easily absorbed. Instead, he occupied the screen like a live wire pulled too tight, capable of snapping or sparking without warning. He was an actor drawn to instability, to characters who talked too much because silence felt unbearable, and to men whose inner lives pressed outward in uncomfortable ways. That instinct shaped his work, defined his reputation, and ultimately framed how audiences came to understand him.

By the time of his death on December 19, 2025, at the age of forty-six, Ransone had amassed a body of work that resisted neat summary. He was recognizable without being famous in the conventional sense. His presence lingered longer than his screen time suggested. Directors returned to him not because he was safe, but because he was willing to go where others would hesitate.

Baltimore Roots and Early Formation

Ransone was born on June 2, 1979, in Baltimore, Maryland, to Joyce (née Peterson) and James Finley Ransone II, a Vietnam War veteran. The city remained a psychological anchor throughout his life. Baltimore’s textures, contradictions, and tensions surfaced repeatedly in his performances, even when the stories were set elsewhere.

After an unproductive stretch in a traditional high school environment, Ransone successfully auditioned for the George Washington Carver Center for Arts and Technology in Towson, Maryland. There, he focused on theatre and fine art, disciplines that encouraged observation and emotional precision rather than polish. Friends later recalled that he was already serious about craft, even as he resisted authority and routine.

He briefly attended the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan in the late 1990s, studying film. The experience ended abruptly when he was expelled for non-attendance. Formal structures did not hold him for long. What did hold him was proximity to working artists. For a time, he worked as a party photographer for Patrick McMullan, moving through rooms filled with celebrities while remaining peripheral, observant, and largely anonymous. It was a position that mirrored his later relationship with fame.

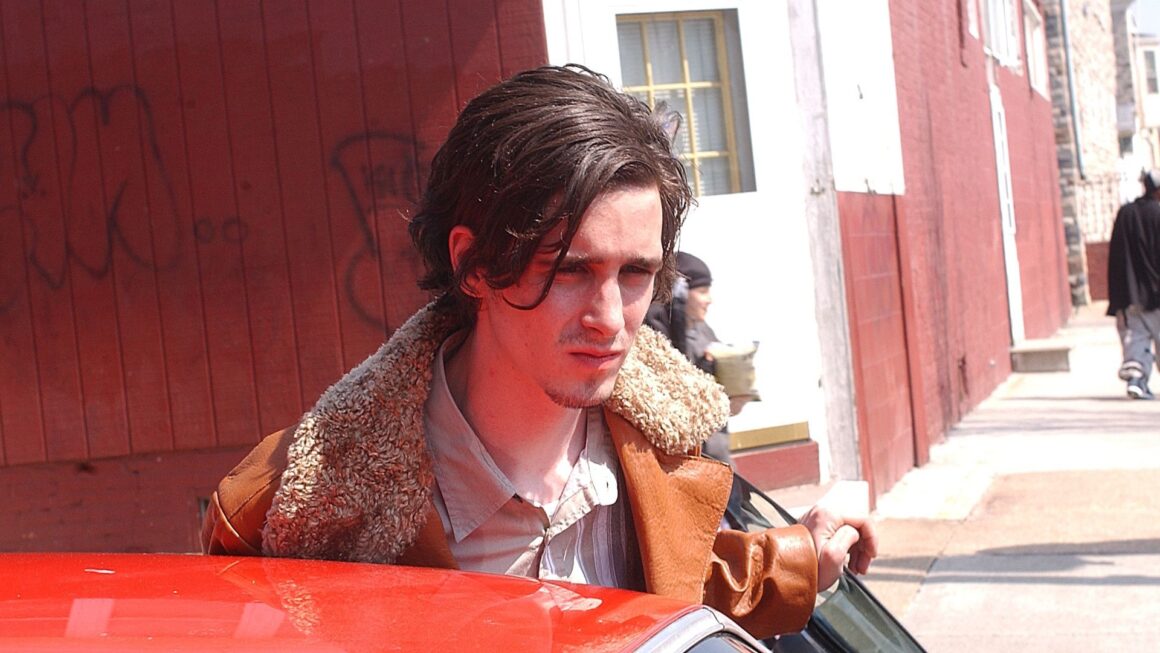

Early Film Work and a Willingness to Risk Exposure

Ransone entered film through independent and art-driven projects rather than studio pathways. His first significant role came in Larry Clark’s Ken Park (2002), where he played Tate, a young man who murders his grandparents. The film was confrontational, and its explicit material left no room for emotional distance. Ransone approached the role without hesitation, later explaining that fear suffocates creative work.

The performance announced the type of actor he intended to be. He was not interested in playing safe or likeable figures. He accepted vulnerability as part of the process, even when that vulnerability made audiences uneasy. That approach would remain consistent throughout his career.

The Wire and the Anatomy of Ziggy Sobotka

In 2003, Ransone joined the second season of HBO’s The Wire as Ziggy Sobotka, the volatile and ill-equipped son of a longshoreman. At just twenty-two years old, and a Baltimore native himself, Ransone brought unsettling specificity to the role. Ziggy was impulsive, needy, and painfully desperate for recognition he could not earn.

What made the performance linger was its refusal to mock or soften the character. Ziggy’s bravado repeatedly collapsed into humiliation. Each failed scheme, from drug deals to theft, ended in public embarrassment. When Ziggy finally committed murder after one humiliation too many, Ransone played the aftermath not as shock but as surrender. Ziggy waits for arrest, hollowed out.

The show’s slow cultural rise meant that recognition arrived years later. Ransone later remarked on the strange delay between filming and public response, recalling moments when people would suddenly recognize him long after he had moved on emotionally from the role. Over time, Ziggy Sobotka came to be viewed as one of the series’ most tragic figures, largely because Ransone allowed the character’s fragility to remain exposed.

Generation Kill and Emotional Precision Under Pressure

Ransone reunited with David Simon’s world in Generation Kill (2008), portraying Corporal Josh Ray Person during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The role required restraint and emotional accuracy rather than theatrical heroism. Person was garrulous, anxious, and perpetually scanning for reassurance in a system that offered little.

Ransone delivered one of his most respected performances here, capturing fear without collapsing into melodrama. His portrayal reflected a lived-in understanding of instability. Shortly before filming, Ransone had become sober after years of heroin addiction. That proximity to crisis shaped the work. The performance felt unfiltered, grounded, and quietly devastating.

Simon later described Ransone as capable of absurdist humor one moment and heartbreak the next, able to pivot without warning. That volatility became one of his defining strengths.

A Career That Refused a Single Lane

For years, The Wire remained a double-edged sword. Ransone openly admitted fearing that he had reached a peak too early, uneasy with the idea that his most celebrated work might already be behind him. Rather than chasing repetition, he continued moving between film, television, and theatre, rarely settling into a fixed category.

He appeared in Spike Lee’s Inside Man (2006), then later collaborated with Lee again on Red Hook Summer (2012) and Oldboy (2013). Lee valued Ransone’s unpredictability, casting him in roles that required tension rather than reassurance.

During the same period, Ransone worked with Sean Baker on Starlet (2012) and later Tangerine (2015). In Tangerine, shot on iPhones across Los Angeles streets, Ransone played Chester, a pimp whose betrayal ignites the film’s momentum. He brought an uneasy charm to the role, grounding an otherwise frenetic narrative with emotional credibility.

Horror as a Space for Uneasy Humanity

Ransone became a recurring presence in horror films, though never as a stock figure. In Prom Night (2008), Sinister (2012), and Sinister 2 (2015), he played figures connected to law enforcement, men drawn toward danger without fully understanding it.

His role as Deputy So-and-So in Sinister stood out precisely because he refused to play the character as disposable. Curious, overeager, and unsettlingly affable, his deputy lingered longer than expected. Audience response was strong enough that Sinister 2 repositioned him as the lead, an uncommon trajectory for a sequel.

In Kristy (2014), he portrayed a campus groundskeeper murdered by a cult. In The Black Phone (2021), he played Max, the brother of a serial child killer known as the Grabber, grounding menace in realism rather than spectacle. He returned briefly in Black Phone 2 (2025), closing a narrative loop without overstating his presence.

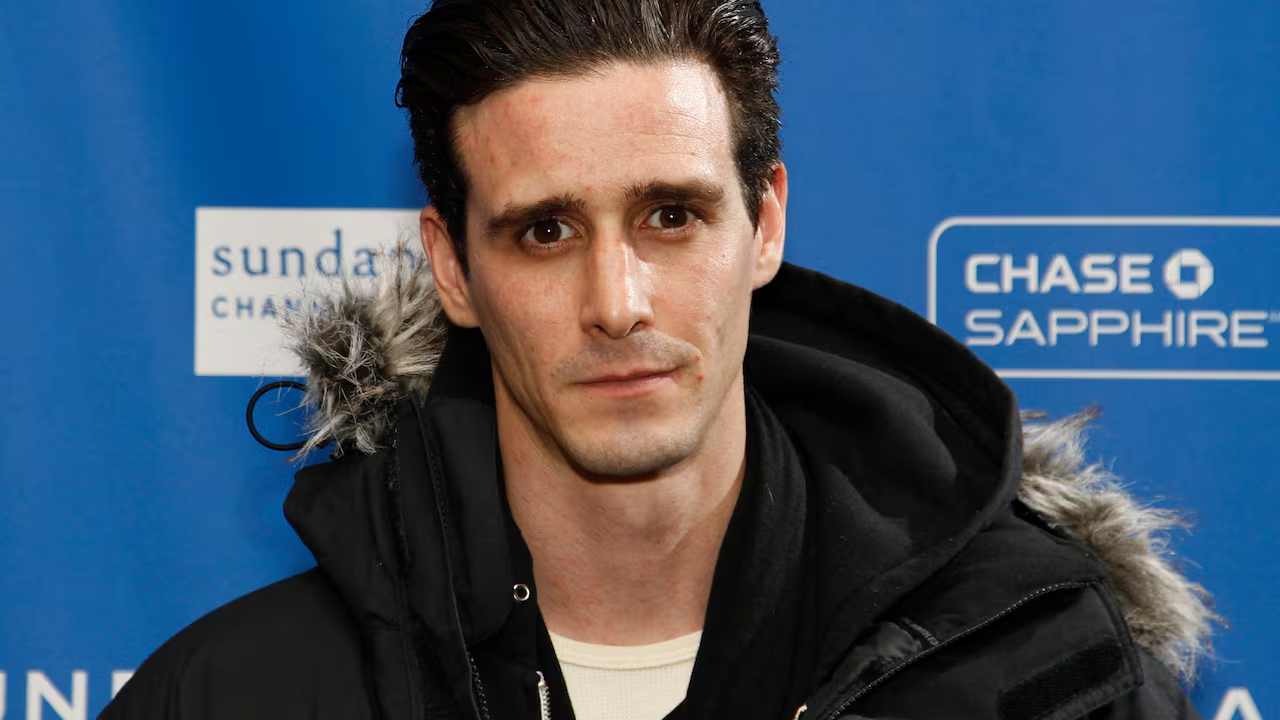

It Chapter Two and the Weight of Childhood Fear

Ransone reached his widest audience with It Chapter Two (2019), portraying the adult version of Eddie Kaspbrak. Sharing the role with Jack Dylan Grazer, who played Eddie as a child, Ransone leaned into anxiety without turning it into caricature. His Eddie was brittle, defensive, and deeply wounded, still living inside childhood terror.

The film’s box-office success brought new visibility, but Ransone remained wary of acclaim. He had long resisted defining himself by popularity, preferring projects that allowed space for emotional risk.

Theatre Work and Sustained Intimacy

Ransone never abandoned the stage. In 2013, he starred in Small Engine Repair off-Broadway at the Lucille Lortel Theatre. The role demanded sustained emotional exposure and confrontation. He later reprised the role in the 2021 film adaptation, carrying years of lived experience into the performance.

The shift from stage to screen revealed one of his core strengths: an ability to maintain intensity without exaggeration, allowing discomfort to sit unrelieved.

Addiction, Recovery, and Speaking Without Cushion

By his late twenties, Ransone had developed a heroin addiction and accrued significant debt. He entered rehab in 2006 and became sober shortly thereafter. He spoke about recovery candidly, framing it as survival rather than triumph.

In 2021, Ransone publicly disclosed that he had been sexually abused for several months in 1992 by a math tutor. He described the abuse as a source of lasting shame and confusion, directly connecting it to later struggles with addiction. Although he reported the abuse to authorities, charges were not pursued.

In the same disclosure, he acknowledged that at the time he quit drugs, he had been contemplating ending his life, explaining that substances no longer silenced the noise in his head. The statement was stark, unadorned, and unprotected.

Later Career and Final Appearances

In the years leading up to his death, Ransone continued working steadily. He appeared in Bosch, Mosaic, The First, SEAL Team, and Poker Face, where he played a thief who kills a man and hides the body in a Christmas display. The role reflected his continued attraction to moral discomfort.

He did not retreat from difficult material. If anything, his choices suggested a deepening commitment to honesty.

Personal Life and Advocacy

Known to friends as PJ, James Ransone maintained a deliberate separation between his professional life and his private world. While his work placed him in emotionally exposed roles, he guarded his personal relationships carefully. He was married to Jamie McPhee and was the father of two children, Jack and Violet. References to his family were rare in interviews, and when they did surface, they were brief and protective rather than explanatory. For Ransone, privacy was not an affectation but a form of care.

That instinct for protection extended to how he spoke about pain. When he discussed his struggles with addiction, he did so without theatrical framing or self-mythology. He described sobriety as a necessity rather than a victory, a decision made because the alternative had become unlivable. His reflections resisted inspirational language and instead focused on endurance, accountability, and the daily work of remaining present.

In 2021, Ransone publicly disclosed that he had been sexually abused as a child by a tutor. The statement was direct and unembellished. He did not present the disclosure as closure or healing, but as context. He spoke about long-term shame, confusion, and the way those experiences shaped his later relationship with substances and mental health. By refusing to simplify the narrative, he pushed against the expectation that disclosure must arrive with resolution.

That honesty positioned him as an important public voice for survivors whose lives do not reorganize neatly around recovery. He did not offer solutions or slogans. What he offered instead was visibility, an acknowledgment that damage can coexist with work, family, and ongoing effort. For many, that candor carried as much weight as any of his performances.

Death and Public Response

James Ransone died by suicide on December 19, 2025, in Los Angeles. He was forty-six years old. Authorities confirmed that no foul play was involved, and no further details were released. The announcement landed quietly at first, followed by a steady wave of reflection rather than shock-driven reaction. His death did not prompt scandal or speculation, but a reassessment of a career and a life shaped by openness about struggle.

In the days that followed, his wife shared a fundraiser in support of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. The gesture redirected attention away from the circumstances of his death and toward the systems that support people living with ongoing psychological strain. It reflected the same values Ransone had expressed while alive, prioritizing care, access, and long-term understanding over momentary attention.

Obituaries and tributes emphasized the consistency of his work rather than its peaks. The Guardian described him as a coiled, wiry actor whose intensity was inseparable from vulnerability, noting how those qualities coexisted rather than canceled each other out. That framing resonated widely. Ransone had never tried to conceal fragility beneath bravado, nor had he turned it into a persona. It was simply present, informing his performances and public statements alike.

Colleagues remembered him as serious about craft, wary of shortcuts, and deeply committed to honesty. His death was widely framed not as a contradiction to his advocacy, but as a reminder of the uneven, non-linear nature of survival. In that sense, the public response mirrored the way he lived and worked, resisting simplification and allowing complexity to remain.

Legacy: An Actor Who Let Discomfort Remain

James Ransone III did not leave behind a single defining performance. His legacy lies in accumulation, in the steady refusal to simplify pain or package it for comfort. He played men who failed, men who broke, men who wanted too much and understood too late.

He trusted audiences to sit with discomfort. He trusted directors with vision. He trusted fear less than most.

What remains is a body of work that still feels alive because it was never smoothed into distance. His characters stay close, unresolved, and human.

Post Comment